IDWs Marco Rota "A" cover for

Uncle Scrooge #407, which originally graced an Italian

2008 reprint of the

1961 Romano Scarpa story that

Scrooge #407 presents using Joe Torcivia's newly-Americanized title "The Duckburg 100":

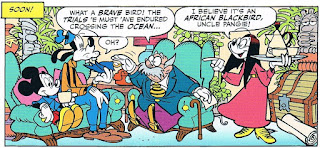

In contrast with his other stories presented by IDW thus far, Scarpa's "The Duckburg 100" is a relatively humble, down-to-earth, domestic, Duckburg-based story. Almost a pure character piece, its lack of big set pieces shouldn't be mistaken for a lackluster read -- its execution is more complex than the premise might suggest. (The most "adventurous" thing that happens is a Beagle Boy robbery during which they accidentally kidnap Donald, and it's mostly played for laughs: the Beagles are just doing what they can't help themselves from doing, and Donald's stumbled into quite a jam, ho-ho!) While the hook -- the bank's contest -- is frankly dry, to the point that it can only be relayed via dialogue, the closest to a visual representation being promotional posters that Scrooge is pleased to see as he nears the bank... really, just more text! In many modern duck and mouse comics, the MacGuffin is something visual and wacky, which can make a story seem contrived and gimmicky. "100"'s more conscientious (and real-world plausible) situational (rather than conceptual, i.e. gimmicky) premise triggers reactions and an ensuing series of event that make Duckburg more believable than usual. Of course, this illusion hinges upon Scarpa's grasp of these characters, which here is wildly apparent. The end result is a quasi-social satire that isn't acidic and vitriolic, but certainly acute.

It's completely logical and in-character for Scrooge to be anxious to the point of obsession, allowing Scarpa to show us -- and amuse us with -- Scrooge in one of his panicked, skittish, somewhat neurotic modes. But Scarpa's Scrooge, like Barks', has varied moods, and so once he's processed the situation, Scrooge quickly turns energized, driven, and determined in taking efforts to ensure that the three contestants each a prove winning bet (on

his end of the deal, of course). To pull off such a drastic transition in temperament as part of staggering a character's reaction to a plot development, keeping the character so true to what makes him tick, is testimony to Scarpa's talent and intuition. And I've almost overlooked how at first, Scrooge was all in favor of the contest and personally commending the bank's manager, only freaking out when he realizes that he owns the bank -- a variation, I believe, of a gag I'm pretty sure Barks used at least once, here executed with a quick setup and then, bam, a blunt turned-on-its head reveal so stark in its irony and so precisely "acted" as to be worth of Laurel and Hardy.

While I would qualify "100" as a character-oriented story before I would a social satire I would say that there is an element of social satire at play. It's predominantly character-driven in that the entire premise is a juxtaposition of the frugal, disciplined, finance-literate Scrooge against three, count 'em, THREE foil types: Jubal, the con artist; the Beagle Boys, who are no-muss, base-level thieves; and Donald, who is (at least in this portrayal) a pure fool. The pop culture-infatuated, financially inept, adult responsibility-oblivious, completely infantile Donald in this story doesn't exactly contradict his general comic book characterization; these traits have been shown, but here, it's just that he's been so completely consumed by these tendencies. I suppose we can chalk it up his obsession with Captain Retro-Duck being a relatively new phenomenon. In other words, a case of, "Oh, it's just a phase -- he'll move on, eventually."

...oh, but I was trying to make a point about the satirical aspects of the story. Basically, Scrooge and his three foils each represent an archetypal human trait/tendency. And each is used to show how money, and moreover, the institution of banking, rules our material existence. Now, I'm not sure if any point is made about this societal situation, which is why ultimately, this is an exercise in showing how these characters each react to a given situation (Scrooge from a different perspective than the other three). But there's at least the framework of a social satire built in to the story.

There is, of course, Scarpa's stab at modern art... which is an easy target, admittedly, but when an

actual artist curmudgeonly vents about it in his own work, it has a particularly relishable sting to it. (And evidently, Scarpa and Barks were fellow curmudgeons, sharing a similar view on this "medium"!)

Is there a moral? Since Donald in the end gets as a reward the very thing the very thing he wanted in the first place, perhaps the moral is, "It's okay to be a fool; just don't be a con man or a low-rent thief." How does Scrooge make out? With all of the angst and obsessive effort he goes through, you might think that there might be some ultimate message about Scrooge being too whatever... but in the end, he gets what he wants, too: he hasn't lost anything. Are Scarpa's sympathies actually with Scrooge? Is he actually endorsing Scrooge's ways? I'm not sure, but I wonder.

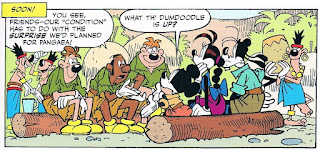

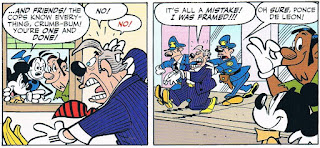

One of Scarpa's many clever accomplishments in his plotting is the way that each of the three contest participants' efforts "cross over" with and impact each other, leading to the outcome of the story. These scenarios are fully developed enough to not feel contrived; in fact, they play a major part in the story having a tone of tasteful and thoughtful whimsical farce. (However THAT is conceivable!) Jubal's storyline is actually phased out, wrapped up prematurely in dialogue between Scrooge and the bank manager -- during which Jubal is off-screen, and after which he remains so. But even that kind of just falls away in the flow of things. The only plot turn that I found abrupt was how easily and quickly things were wrapped up once the nephews got the info via walkie-talkie from Donald, hiding in the Beagles' midst. I expected Donald getting discovered and the Beagles getting the upper hand again, resulting in one last major obstacle to overcome. I commend Scarpa for using what at first seemed like a lark, Donald's being enraptured by his new toy, as an integral plot device, in the dramatic tension afforded by the nephews turning off the walkie-talkie Donald left at home and in how its ultimately the ironic means by which the day is saved. But once Donald finally gets through to the nephews, it's a matter of about three panels before the Beagles have been apprehended (off-screen!), Donald is rescued, and Scrooge has regained the contents of Jewel Vault #3. Nothing to it, easy as pie! Anticlimactic, yes, but at least not as ludicrous and un-sellable as the ending of "Gigabeagle". And not even

half as abrupt.

Now, I could pick on Scarpa for the Beagles' giant suction hose thing being a shortcut intended to expedite the vault robbery scene, and for the awkward, clumsy design he came up with for it... but in the former respect, he actually made the right call, because the story beats felt just right. In fact, I'm surprised by now that I haven't brought up how it's easy to imagine this story's premise as a Barks or Barksian ten-pager. Though it's longer, I guess between the pacing of 10 Barks pages with four tiers each and 33 Scarpa pages with three tiers each, things somehow more or less even out.

For his first turn at a lead story in an IDW Disney comic, Joe Torcivia's dialogue is actually less archaic than that of some of his other recent Americanized scripts... but that's not to say that it's ever dry or straightforward. Take page 8, panel 2: "Hey, you punks! I want my

gold nibs!" "Oops! Old stealing habits die hard!" Straightforward in comparison to, say, the daunting alliteration that opened "Meteor Rights", but imagine what the panel in question could have been: "Hey! You stole my gold nib!" "Oh, sorry! We didn't know it was yours!" Or the last panel on the same page: "

Gadzooks! The hundred's

here! In one

lump sum!" What if that had just been, "Wow! Just what I needed, a check for $100!" It really can be the little things that make one's reading experience with these considerably smarter than could easily be the case.

A significant but necessary amendment to the story that Torcivia has made is the entire "Captain Retro-Duck" angle. Until just now, when flipping to the relevant pages, I hadn't put together that there was no superhero or action TV star of any type shown on Donald's TV screen even once during the story. Thus, if I deduce correctly, Captain Retro-Duck, who is referenced in Torcivia's version of the voiceovers for the walkie-talkie promo spots Donald salivates over, was conceived to justify for contemporary American readers why in the age of Google and iPhones Donald or anyone would get so excited in the first place about a walkie-talkie set. It's not that Captain Retro-Duck is a retooling of the TV action star in the original version; there was no TV action star in the original version! In that case, when Donald wanders off from home lost in "playing" Captain Retro-Duck, does that mean in the original, he was just playing some sort of generic make-believe spy game? I can't help but think that his frivolities seem more justified in Torcivia's version. And the nods to TV/comic book/superhero/sci-fi etc. fandom that he worked in are an added bonus, as are all the punny variations of the prefix "retro". Exemplifying both, we have "Sinister storage tanks! Just like the dreaded

Eviloid in Episode 213: 'Captain Retro-Duck and the Retro-gressive Gas!'"

_____________

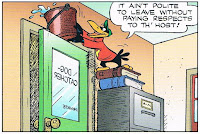

Scrooge #407 wraps up with a two-page Tony Strobl gag created for the Disney Studios program. In contrast with the nephews' chastisising and being considerably wiser than Donald in the lead story, here, they're shown as being completely on the same page and virtually standing as one with Donald against Scrooge. The gag boils down to Scrooge "programming" a parrot to say a series of things to "brainwash" his nephews, and in retaliation, they "reprogram" it to say the things that Scrooge decidedly doesn't want to hear. It reduces the characters to one-note roles... but that's sort of the nature of gag pieces. And as far as gags go, it's decently constructuted, as crass as it makes the characters seem. And I am glad that it's finally be printed in the States, for better or worse.

(Hmm, it just occurred to me... with Strobl, it's kind of as if the characters had been done by Hanna-Barbera. Or the Disney characters done by the artists who drew Western's Hanna-Barbera titles... one of whom I'm sure was Strobl. But he was also a product of his era. I can see some commonalities between him and even the original animation featuring the classic Disney cartoon characters produced for framing sequences of the

Walt Disney Presents/

Wonderful World of Disney episodes that were made up of select theatrical shorts. But I digress... )

_____________

Though I definitely think of Marco Rota's "A" cover, above (at the start of this post), as the "definitive" cover of this issue (for its "classic" duck comic look), I couldn't help but also purchase a copy with James Silvani's "sub" cover variant. It hit me in a soft spot for evoking DuckTales (i.e. due to the dynamic of Scrooge and the nephews sans Donald, and how, rather than their shirts being "blacked in", the nephews are sporting their DT-canonized red, blue, and green shirts), and "Treasure of the Golden Suns" in particular. The Junior Woodchuck coonskins were prominent in that serial, which may have been the first time the nephews were seen wearing them in conjunction with their non-blacked-in, then-newly-canonized-color scheme-complying shirts. So the aesthetic of their being so attired has a distinctly DT air to it.

-- Ryan